After watching the film, I definitely agree that the notion of firms being “too big to fail” still exists today, and in more industries than just investment banking. The 2008 financial crisis showed that investment banks are interconnected and rely on each other’s financial wellbeing. In the film, this interconnectedness could be seen after the Lehman Brothers’ bankruptcy filing. Investment banks saw immediate hits to their businesses as a result of the dwindling confidence in the industry. Other firms, such as GE, saw that their operations were affected by the lessening access to capital from investment banks. To the dismay of many, the notion of “too big to fail” means that the government may be required to aid the financial system at large when the market is unstable. Continue reading

Tag Archives: Investment Banks

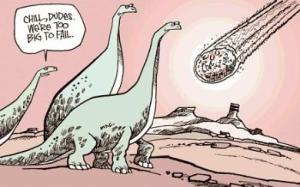

Moral Hazard

I think that the concept of “too big to fail” still exists today, as the financial services industry is still an oligopoly with few banks controlling the fate of the economy. If, for example, a company like Citigroup, J.P. Morgan, or Bank of America were to go under at some point, the economy would fall apart. Though it has tried to address the concern that banks could dismantle the financial system by regulating proprietary trading, capital requirements and others, the government has not addressed the problem of “moral hazard,” where investment banks take bigger risks because they are dealing with other people’s money and not their own. The way to reform the banking system is to shift the risk to those that make the decisions to take the risk in the first place. Continue reading

Too Big-headed to Fail

After watching “Too Big to Fail”, it is clear to me that this notion still exists today. The last piece of information you are left with is that 10 banks hold 77% of all American assets. Wow. These banks own more of our tangible country than the government does. These banks cannot fail. With our nation’s money invested in keeping them alive, another downward spiral will cause the government to loose all the money they had to save the banks this time around. The banks failing in the film were too big because they were responsible for pensions, salaries, life’s investment, college funds, etc. If these banks went under, too many lives would be affected. But now, it’s not very different. All of those same concepts apply but now the government’s money is invested. The banks cannot fail, because then our economy fails. The government would be too low on cash.

An issue I also saw at the end of the film was that the banks are not the only entities that are too big to fail. Our government seems the same way. Only the government seems too bigheaded to fail. In the movie, Paulson “stuck to his guns” about not giving bailouts and instead placed government investments into the banks, just so that he could keep his word. We even see it today with other issues as our government is “taking a break”. People cannot compromise and find solutions because they are stubborn. Yes, it is important to stand up for what you believe, but when your position effects the lives of an entire country, sometimes you need to think of the best interests of the general good, not what you personally believe to be good.

The Ultimate Fiscal Consolidation

The notion of “Too Big to Fail” not only still exists today, but it is even more relevant to our current financial system in the United States than ever before. As shown in the film, the ‘great recession’ of 2008-2009 ultimately marked the first time that people really started to question the size and power of some of our largest financial institutions. Up until this point, US Banks, for the most part, were perceived as highly respected and admired institutions that were a symbol of America’s economic strength. Rather than limiting the size of these banks, popular opinion of the 1980s and 1990s was that it would be in our best interest to let them grow as much as possible so that they could effectively compete with giants of the industry abroad in Europe and Japan. Ultimately, it was this popular belief, coupled with pressure from Wall Street’s most powerful figures, which prompted arguably the most notable piece of financial legislation of my life time: the Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act of 1999. Under this law, the concept of ‘Universal Banks’ reemerged in the US for the first time since the 1930s as investment banks could once again participate in commercial banking activities and vice versa. Ultimately, it was this change, commonly referred to as the fall of Glass-Steagall , that set the stage for the emergence of institutions that are in fact ‘Too Big to Fail’.

As shown in the movie, major financial institutions played a pivotal role in the financial crisis, some for good reasons and others for very bad reasons. Clearly, it was the irresponsible and overzealous actions of numerous institutions that directly contributed to the crisis. Yet at the same time, it was the cooperation of the whole industry that ultimately helped to save it from a complete collapse. That being said, one of the most significant outcomes of the 2008 financial crisis was a wide scale consolidation of Wall Street. Prior to 2008, there were dozens of banks that were seen as significant financial institutions in terms of size and market share. However the crisis completely changed the layout of the industry as the strongest banks seized control of the market. As noted in the film, 10 banks now control 77% of all US bank assets and, even more staggering, the six largest banks control 67% percent of total assets (http://consciouslifenews.com/big-fail-bigger-before/1165613/). Although there has been a slight resurgence over the past couple of years, the number of mid-size and boutique banks dropped substantially as they did not have the financial might to withstand the crisis and so were forced to declare bankruptcy or be acquired by megabanks such as J.P. Morgan or Bank of America.

Seeing these staggering market share figures, it is hard to argue that the notion of “Too Big to Fail” no longer exists. All of these banks that were deemed critical to the US economy in 2008 are now bigger and therefore even more critical than ever. Ultimately, without these banks, the US economy would likely cease to be relevant and if that doesn’t mean that they are ‘Too Big to Fail’ then I don’t know what does.

To conclude this post, I would like to point out that most believe that the solution to this problem would be to simply reduce the size of the banks. While this is probably a smart idea, I strongly believe that the size of the banks was not the cause of the crisis and that all of the support to reinstate Glass-Steagall is not warranted. The main reason that our banks are still considered some of the strongest in the world is because they are not limited to choosing between being an Investment Bank or a Commercial Bank. Where was J.P. Morgan 20 years ago? While it was certainly a strong bank, it was not considered one of the 10 most powerful in the world. And now, along with the likes of Goldman Sachs and other US banks, it is arguably the most respected institutions in the world. Once again, the problem with our financial system was not that banks were getting big, but it was their ability to take on too much leverage due to the lack of strong regulatory agents in the US. I have attached an insightful article below by one of our own professors, William Gruver, which speaks more about this issue.

Room Full of Trillions

The scene that intrigued me the most, was when Henry Paulsen invited all the CEO’s of the big banks to come together and meet at a round table to try and save Lehman Brothers. That room was full of people who together controlled a ridiculous sum of money. Yet, all I kept thinking about was how they are just human beings weighing their options and trying to make decisions that are either best for their companies, themselves or both. The CEO’s in the room included: John Mack (Morgan Stanley), John Thain (Merrill Lynch), Jamie Dimon (JP Morgan), Lloyd Blankfein (Goldman Sachs), and Vikram Pandit (Citigroup).

The scene that intrigued me the most, was when Henry Paulsen invited all the CEO’s of the big banks to come together and meet at a round table to try and save Lehman Brothers. That room was full of people who together controlled a ridiculous sum of money. Yet, all I kept thinking about was how they are just human beings weighing their options and trying to make decisions that are either best for their companies, themselves or both. The CEO’s in the room included: John Mack (Morgan Stanley), John Thain (Merrill Lynch), Jamie Dimon (JP Morgan), Lloyd Blankfein (Goldman Sachs), and Vikram Pandit (Citigroup).

I will now try to write a dialogue as if I was at this round table discussion, and had the undivided attention of these CEO’s.